Archery is a fantastic hobby, evolved from some of humanity’s earliest exploits, both as hunter-gatherer, as protector, and inevitably as time went on, as warrior.

Today, it’s still used a lot by hunters – especially in predator-rich environments, but it’s also fantastic fun for archers of all ages, an exercise in discipline and refinement, and a well-respected sport all over the world.

In this post, we'll cover:

What Is Archery?

Archery is the art of shooting arrows, by use of a bow. It’s also the expression of a series of very good ideas, rendered into reality by human beings as they evolved.

It’s widely thought by historians that archery originated in the Stone Age.

So a) yes, we’ve been doing this a really long time, and b) no, there were probably never bows made of stone. Or if they were, they probably failed to work in a very big hurry, and their inventors were probably eaten.

That’s point #1 about the history of archery. It probably began as an evolution of the thought “If I can stick this sharp thing in that dangerous animal from quite some way away, it’ll be dead before its claws can rip me open, and I’m eating lion tonight.”

The History Of Archery

In the Stone Age, a time before large-scale farming, lots of the good eats around had claws, fangs, horns, an awkward home environment like the water, or a really bad attitude.

You had to grab any strategic advantage you could get if you were to win any encounter with them. Winning meant protein, and protein meant strength, speed, stamina – and quite possibly, even mating rights.

Distance from your prey is an incredibly useful advantage in the ‘kill, but don’t get killed’ stakes. It’s a strategy used by amphibians with their long, insect-catching tongues. By fish that hide under sand and shoot spikes at their prey. And by lots of other predators in the animal kingdom.

Humans are many things. Patient is not one of them. Refusing to wait the millions of years it would have taken to evolve the likes of projectile bone-spurs from our wrists, we did the next best thing. We whittled branches into sharp, aerodynamic points, and then we flung them at our hoped-for dinner.

Spear-throwing probably got us many a meal before we first considered the idea of the bow. A piece of bendable wood that could be strung and used to fire smaller sharp projectiles further distances towards our would-be prey.

At about the same time as we were working out that sharpened pieces of stone could be used as tools for a whole range of tasks, we were working out how to make ourselves a safer, longer-distance killing machine.

Archery in its rudimentary form was born around 20,000 years BC, according to the historians.

The first time those historians have records of people getting involved in archery is some 17,000 years later in ancient Egypt.

Think about that for a second. Even in terms of recorded archery, it’s been around for 5,000 years.

It’s also been responsible for turning the tide of history many times.

Those first records we have of ancient Egyptian archers show that in the period between when it was probably first developed and when it was first recorded, human beings had had another important thought. The Egyptians were adept at using archery both as a source of food and as a tool of war.

Tools of war rarely, if ever, go away.

By the time of the Shang Dynasty – 1766-1027BC –China had archers.

The Greco-Roman period has left us lots of depictions of archers, shooting both for meat, and for war.

China introduced archery into Japan in the sixth century, and on it went…

European history was frequently determined by archery. Probably the Norman conquest of England was decided by the skill of Norman (French) archers, establishing a dynasty that went on (with wars in between) for over 400 years.

The Native Americans had the skill of archery and were able to use it well. But in their case, the arms race went against them as they lived in the age of Europeans with guns.

As archery was outstripped as a tool of war, it became more a thing of sport for some, and reverted to a tool for hunting for others. That’s where it still is today – sport, fun, discipline, and a hunting technique for plenty of people around the US, and around the world.

Types Of Archery

Because it’s had so many uses and styles throughout history, there is a fairly broad spectrum of ‘types’ of archery to choose from today.

Even among the most popular types, you can choose to shoot:

· Field archery

· 3D target archery

· Target archery

· Traditional archery

· Bowhunting/Bowfishing

· Mounted archery

Let’s take a quick tour through the pleasures and pitfalls of those different types of bow sport.

Field Archery

Field archery is most often done out in the wild – usually in the woods or other challenging terrain. Targets are set up at various distances, and those distances will usually be unmarked, adding to the difficulty and the skill of the shoot.

Several organizations exist which hold regular field archery competitions, including the National Field Archery Association (NFAA) in the US, the International Field Archery Association

in the US, the International Field Archery Association (IFAA), and World Archery

(IFAA), and World Archery (WA).

(WA).

Field archery competitions set up by the NFAA or the IFAA generally include three rounds – field, hunter, and animal rounds. Each round consists of 28 targets, in two units of 14.

set up by the NFAA or the IFAA generally include three rounds – field, hunter, and animal rounds. Each round consists of 28 targets, in two units of 14.

Field rounds are set up at ‘even’ distances up to 80 yards. Targets have a black inner ring, two white middle rings, and two black outer rings. Depending on the distance to the target, four different face sizes can be used. You score five points for any shot hitting the center spot, four for shots within the white inner ring, and three for any arrows in the outer black ring. Any further out than that and you get to go on an arrow hunt!

Hunter rounds use ‘uneven’ distances up to 70 yards. The scoring in hunter rounds is the same as in field rounds, but be aware – the targets look different. The whole scoring zone in hunter rounds is black save for the center ‘bullseye’ ring, which is white. The black outer rings are still divided into inner and outer rings though, giving you the difference between your four-point zone and your three-pointer.

Animal rounds are shot at uneven distances, but the targets are 2D animal targets. As you might expect, animal targets change both the rules and the scoring.

You get three chances to hit the target, one from each of three stations. Hit the target from station #1, and you’re done. Hit it from station #2, likewise.

Scoring is more visceral on animal targets than on plain ones. There are three vital zones, marked for 20, 16, or 12 points respectively, and three non-vital ones, which score 18, 14, and 10 points.

3D Archery

3D archery uses 3D animal targets for a more authentic hunt-shooting experience.

Targets in 3D archery are set at random distances, and even random angles, so as to more effectively represent the prey animals in whose shapes they’re made.

The scoring in 3D archery is more complicated than on 2D animal targets – there are inner and outer rings for each point value on the target, but those point values differ, depending on the target itself.

One thing you’ll find the further into archery you’ll go is that almost every type of archery has its own organizations. In 3D archery, you’re looking at the IBO (International Bowhunting Organization) and the ASA (American Shooters Association)

and the ASA (American Shooters Association) to organize tournaments.

to organize tournaments.

Target Archery

Target archery is very often the first sort of archery you encounter because it’s the easiest environment in which to teach large groups of people the basics of shooting a bow. It can be shot all year round, inside or out, and because it’s stationary, with relatively large targets with ten scoring rings, it’s well suited to beginners. The targets can be moved to different differences, to let those who are relatively new to the sport hone their eye and their skills, and it’s also open to archers using a wide range of bows, from recurve to longbow, and from compound to barebow.

You can also shoot competition target archery inside or out. Indoors, you’re looking at distances of 20 yards. Outdoors, you start from 27 yards and can go as far as 90 yards.

Competitions are divided into ‘ends’ of either 3 or 6 arrows a time. Each archer adds up their score after each end. The pressure comes from an additional ticking clock element though – on 3-arrow ends, you get just 2 minutes to shoot the three best arrows you can. On 6-arrow ends, you get 4 minutes.

The combination of easy access training, and competitions with the added pressure of time on every arrow you shoot, makes target archery popular with beginners and fiercely cut-throat in competition.

Traditional Archery

Traditional archery is less competition intense, more get-back-to-nature fun than standard archery. It includes everything from longbows carved from a single tree to recurve bows with wood in their heart. Traditional archery is less a specific competition discipline, and more a philosophy of bowmanship.

with wood in their heart. Traditional archery is less a specific competition discipline, and more a philosophy of bowmanship.

Traditional archery has nothing to aid you in terms of accuracy. It’s you, the bow, the arrows, and whatever you’re firing at. You will need things like arm-guards, but overall, a stripped-back, aim and shoot simplicity is the heart of traditional archery.

Bowhunting/Bowfishing

Bowhunting and bowfishing are less known as competition sports than some of the other forms of archery – though of course, it’s easy to frame them as competition. More often than not, though, bowhunting and bowfishing simply the disciplines of hunting game or fish through the medium of the bow, like our ancestors did.

Mounted Archery

Since the rise to prevalence of the gun, mounted archery as a tool of war has waned in the Western world. But the combination of skill and discipline in mounted archery has seen it enjoy a renaissance in recent years. The Mounted Archery Association of the Americas promotes the sport, and there are affiliated chapters of the Association all around the country. In a nod to the mounted archers of centuries past, there’s a great emphasis placed on equestrian care, grooming, and training.

promotes the sport, and there are affiliated chapters of the Association all around the country. In a nod to the mounted archers of centuries past, there’s a great emphasis placed on equestrian care, grooming, and training.

The traditional mounted archery course runs over 295 feet. Archers ride the course with no reins, and the targets are positioned at uneven distances.

Mounted archery is the bowhunting of competition archery, taking you back to the thrill, the adrenaline-ride of our ancient ancestors.

Things You’ll Need To Be An Archer

Bow

The type of bow you choose is up to you, but you need to make sure your bow is weighted within your comfortable draw length and draw weight.

Your draw length is the measurement of how far back you can pull a bowstring. Your draw weight is the amount of force (in pounds) needed to pull back a particular bowstring. Between them, these two measurements will determine your ‘size’ of bow.

It’s worth remembering that with longbows and recurves, the draw weight increases the further back you pull the bowstring. compound bow on the other hand have set weights all the way through the draw.

How do you work out your draw length and draw weight?

How do you work out your contact lens prescription? You probably don’t – you probably go to a professional who can tailor it for you. It’s more or less the same deal with draw length and weight.

Draw weight takes a standard of 28 inches of draw length, and then determines your comfortable draw weight in pounds at that length. You need access to a solid handful of incrementally heavier bows and at least a second pair of hands to accurately measure your actual draw length while you have your arm extended.

Go see a bow-tech at your local archery store. They’ll be able to fit you comfortably for the bow you want. Your bow will be marked with a notation like 35#@28” – 35 pounds of draw weight at 28 inches of draw length. Once you know that notation, you can pretty much pick up any bow with the same notation and be confident of getting repeatable results with it.

Bowstrings

The bowstring is likely to be the part you’ll replace on the most regular basis. Also, the bowstring you need will depend on the bow you choose. Traditional archers can use bowstrings of natural fibers like linen, hemp, or even rawhide.

More modern bowstrings can be made of anything from Dacron (a kind of high-strength polyester) to ultra-high-molecular-weight polyethylenes (go ahead, try saying that after five beers, we’ll watch and laugh), like Dyneema.

Match the right bowstring for you to the bow you use, but always take some spares with you when you shoot. If your string breaks while you’re shooting, not only will you get a bruise to shame the gods, but if you don’t have spares, that’s you, done with shooting for the day. Go prepared, and you can keep strung and carry on.

Arrows

Just as with the right bow, you’re going to need the right arrows. Right in length, right in weight, right in the kind of tip you’re using.

In terms of length, go for arrows an inch beyond your draw length. That ensures that when you’re at full draw, they stay straight and connected, rather than drooping and running the risk of impaling you through the foot when they’re loosed in panic.

Other factors to consider include the ‘spine’ (or bendability) of the arrow. How bendable do you want your arrow? It’s a Goldilocks problem. You’re looking for arrows that are ‘just right’ for you and your bow. You want some bend, because arrows that are overly rigid shed precision and accuracy like a brain surgeon on a bar hop. But you don’t want too much bend, because then what you end up with is an arrow with self-esteem issues, that spirals into the ground at the first opportunity. Jusssst enough spine for the weight of the bow and the length of the shaft will do nicely, thank you.

Girth’s important too. Depending on your background and life experience, this may not be news to you. Thicker arrows are better for target archery, because they have a better chance of touching a ring line and upgrading your score. Thinner arrows work better in outdoor environments, shrugging off the effects of wind better than their chunkier counterparts.

When people talk about things being “straight as an arrow,” they’re not just plucking a phrase of thin air. The straighter the arrow, generally, the more likely they are to do as you tell them.

Wait, hang on, aren’t all arrows straight?

You might be surprised. Certainly, most arrows are straight-ish. But once you know that straightness is a desirable factor, you can devise a matrix of arrow straightness, and you can charge more for arrows that are straighter.

Nock

The nock is the notch at the back of an arrow, which keeps the arrow stable as you draw, and helps translate the motive force of the drawn bow to the arrow and propel it into flight.

The type of bowstring you use will differ depending on the kind of archery you’re shooting. That means there’s a need for a variety of nocks, to best grip the bowstring you use.

Fortunately, for beginners, the nock is usually sold as part of the arrow.

Quiver

The quiver is a simple arrow-purse, to give you quick and easy access to your arrows when you need them.

They come in two kinds – the back quiver and the hip quiver. All the archers you’ll see on TV and movies will favor the back quiver.

Why? Because it’s cool, that’s why. It’s out of the way, and it encourages the coolest move ever in heroic fiction – the simultaneous bow-ready and arrow-grab that turns a bow into a weapon of surprise.

Back quivers are an entirely legitimate choice, but plenty of target and field archers instead choose a simple hip quiver, for speed of access. Target quivers tilt the arrows’ feathers forward for easy reach, and field quivers frequently have tubes for individual arrow storage.

Finger Tab

Finger tabs are simply pads (usually split, for use when drawing back the bow with the arrow nocked) which save you from pain, finger numbness, and eventual loss of accuracy when drawing your bow. Sometimes, especially when using compound bows , you can get mechanical release finger tabs, which take some of the stress out of your fingers.

, you can get mechanical release finger tabs, which take some of the stress out of your fingers.

Arm Brace and Chest Guard

Because of the way you hold and fire a bow, there’s every likelihood that once the arrow is loosed, the bowstring will whack you on the inner arm. Even with lower-powered bows, doing that repeatedly can leave you bruised like you’re in Fifty Shades Of Bow Sport. Doing it with higher-powered bows even once can leave you feeling positively murderous, and disinclined to shoot anymore.

Likewise with chest guards. The primary purpose of a chest guard is to keep your clothing under control and stop it from interfering with the firing of your bow. But as it’s usual in good archery practice to draw the bow to the chest, using a chest guard helps ensure any mishaps – string snaps, collapsing arm form, etc – don’t leave you with a big, painful chest.

A World Of Bows

There’s a bow out there for every archer. Finding the one that speaks to you will be a process of experimentation. But let’s take a stroll through the fantasy bow-store and see what options are available.

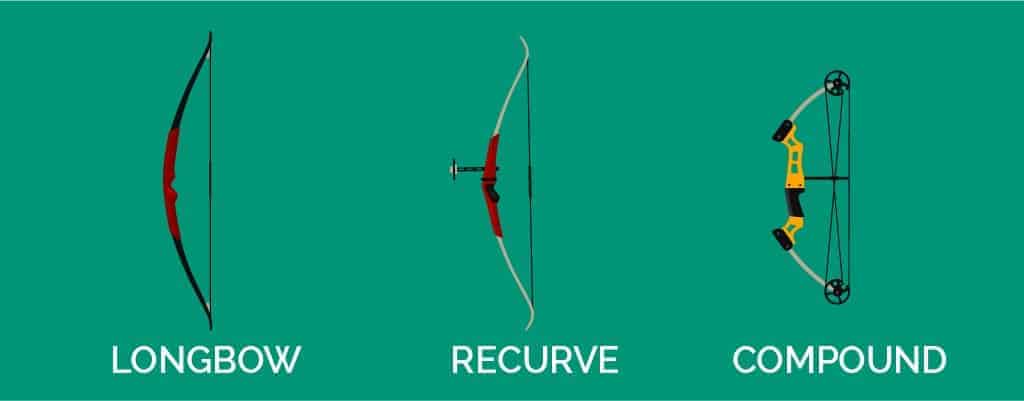

Longbow

A longbow is a tall bow with little if any recurve, usually, but not always, made out of a single piece of wood.

Medieval longbows have a thickness between 33-75% of their width, and bend throughout their full length. English or Victorian longbows, which have a thickness of at least 62.5% of their width, don’t bend throughout their full length. It’s very Victorian, that lack of bend.

The longbow is the friend of purists, historical re-enactors, and traditional archers everywhere because it has no time for fancy sights or counterweights. That means it gives you a simpler approach to archery. If you’re looking to get among the longbow crowd, the International Longbow Archers Association will be able to help you.

will be able to help you.

Flatbow

The flatbow is the American longbow. How different is it from the English version? Well, while it is similar to the tool of European war throughout the centuries, it has a different profile in section, forming an almost rectangular shape, compared to the English D-shape or circular section. While flatbows were used by lots of Native American tribes in the pre-gunpowder age, the modern flatbow goes only as far back as 1930.

Pleasingly, it was originally developed to establish that the English D-shape was superior to rectangular sectioned bows.

It established entirely the opposite of that and has never looked back. In fact, an evolution of the 1930s flatbow is now used as the standard Olympic competition recurve standard.

Still allowing for a more retro feel and a simpler approach to modern archery than many recurve or compound bows, the flatbow combines that historic vibe with a more efficient shooting profile than the ultra-traditional longbow.

Recurve Bow

Recurve bows are bows where the limbs curve away from the archer when the bow is unstrung. They’re popular because they store and deliver more power from each draw than non-recurving bows. That means harder hits, longer distances, and more technical difficulty in competition.

You can shoot recurves in either modern or traditional style. The difference? Mostly the amount of tech and enhancement it will take.

Traditional Recurve

Part of the point about a traditional recurve is that it gives you more power than, say, a flatbow, without involving you in all the fuss of sights and stabilizers. It can give you fast aiming and shooting, rather than necessarily inch-precision on the target. That’s why, for instance, lots of bowhunters still use traditional recurves without all the add-on tech.

Modern Recurve

In the same way that exceptional athletes still wear a kicking, extra-benefit pair of shoes when they take to the track, field or court, if you’re serious about using a recurve in competition, in target or field archery, if you’re not using every technological advantage, chances are you’re going home with neither groove nor glory. Stabilizers and sights are the order of the day with modern competitive recurves. Does it have the purity of look of longbows or traditional recurves? No, it looks like you’ve strapped a Transformer onto your arm. Does it help make you way more of a dead eye, with a chance of getting some highly reliable archery done? Absolutely.

Plenty of competition recurve archers don’t stop at a single stabilizer but keep building out with add-ons to enhance the likelihood of their getting the shots they want. As long as the add-ons are within the rules of the competition, and they don’t adversely affect the weight of the bow, every additional stabilizer and sight aid just helps the archer get the best legitimate shots they can get.

Crossbow

The crossbow is a slightly controversial inclusion in an archery round-up, because to some extent, it’s not a bow in the same way as most bows are in archery. It’s more like the gun a recurve bow dreams of being.

Held with its workings horizontal, rather than vertical, the big difference with a crossbow is that you’re not drawing and holding the tension in the bow yourself. You draw the string of a crossbow until it clicks into place, load the bolt, aim, and fire with a triggering mechanism that releases the tension.

There’s an argument that this process is not similar enough to either traditional or modern ‘archery’ to be included. The crossbow is archery’s ‘missing link’ between the likes of the longbow and the gunpowder age, with a touch of the ancient ballista thrown in. That said, it has a long history of being devastating in battle and has a lot of devotees to this day.

Compound Bow

Compound bows look like half a recurve, with a set of cables and pulleys at the back.

What the cables and pulleys deliver in a compound bow is increased power storage and release without that amount of power being demanded of you personally through your draw. With a compound bow, you can shoot further and easier than you could if your draw was all the power you had to call on.

Compound bows tend to be stiffer and more rigidly constructed than most longbows or recurves, and are a world of their own within archery. They come in four main versions.

Single Cam Compound Bow

A single cam compound bow has just the one cam at the bottom, with an idler wheel up top. That means you don’t need additional cables, but can use just one bowstring as normal. What you get for your single cam compound money is a bow more powerful than an equivalent recurve, but still maintaining an accuracy that connects you directly to the shot.

Twin-Cam Compound Bow

A twin-cam compound bow has two identical cams at the top and bottom of the bow. They’re significantly more powerful than single cam bows. But as you add complexity, you add potential issues too – you need to make sure your cams are well synchronized to get the maximum power out of them. You might also start to need stabilization more than ever, to stop the energy release becoming erratic when you shoot.

Hybrid Cam Compound Bow

The issues that can develop with a twin-cam compound are partly mitigated and solved by a hybrid cam.

How?

Automatic synchronization of the twin cams, that’s how.

That limits the need for stabilization, with the bottom cam providing the power and the top cam synched to it. That means a hybrid cam bow needs less tuning and can deliver you the impressive power and distance of a twin-cam, without some of the issues that come with it.

Binary Cam Compound Bow

The binary cam compound is equivalent to the racehorse of cam compounds. In binary cam compounds, the cable from one cam goes to the opposite cam, and the two cams regulate one another. The practical upshot of that is that you get phenomenal power from a binary cam compound, without the muscle-tearing or shoulder-popping it would require were you dealing with a simple recurve. Also, the self-regulation means you get the minimum kink in your arrow release, for more on-target delivery.

Be aware though – frequent tuning and maintenance is required to keep the binary cam compound delivering at the peak of its performance capabilities.

Takedown Bow

A takedown bow is a bow constructed of various pieces that can be put together to form a working bow and then, when you’re done shooting, ‘taken down’ again for ease of transport. It’s the James Bond version of a recurve bow, breaking down into a central riser, two limbs and a suitable bowstring.

Apart from the great increase in transportation-ease, one of the best elements about a takedown bow is that you can keep updating it as time goes on, getting stronger and stronger limbs as you like, for a more and more powerful bow as your muscles get stronger and more used to shooting.

Reflex Bow

Reflex Bows have limbs that turn away from the archer throughout their length.

What that means is that reflex bows can often be a lot shorter and more compact than recurves, but maintain a high draw weight and a long draw length. The downside of which is a trust factor – the only way the combination of shortness and power works is by putting heavy stress on the materials of the bow.

Given that historically, most reflex bows have been composite bows, there’s always the worry of that stress being too much for the bow. But if you pay good money, you can still get a reflex bow that gives you that unusual combination of shortness and power.

Reflex bows have long been favored by horse archers, and you might well still find them prevalent in mounted archery competitions.

Yumi Bow

The yumi bow is representative of the Japanese style of archery, as practiced by the Samurai in feudal Japan. It comes in two forms, the longer daikyū, and the shorter hankyū bow. The daikyū stands over 6 feet 6 inches tall, and unlike most other bows, it’s asymmetrical, with a grip usually two-thirds of the way down the bow.

Another bow that was initially designed mostly for mounted archery, the yumi depends for its life on a careful maintenance regime. Without such a regime, you can quickly lose the effectiveness of your yumi.

Best Shooting Practice

As with many things in life, there are plenty of wrong ways, and only a few right ways, to shoot a bow.

- Stand up straight, with your feet apart and in line with your shoulders

- Keep your weight evenly distributed on both feet, rather than leaning on either leg

- Relax your knees – you’re aiming to remove rigidity from your posture

- Straighten your back and relax your shoulders

- Stand up straight, rather than leaning either backward or forward

Let’s take a quick look at the best practice.

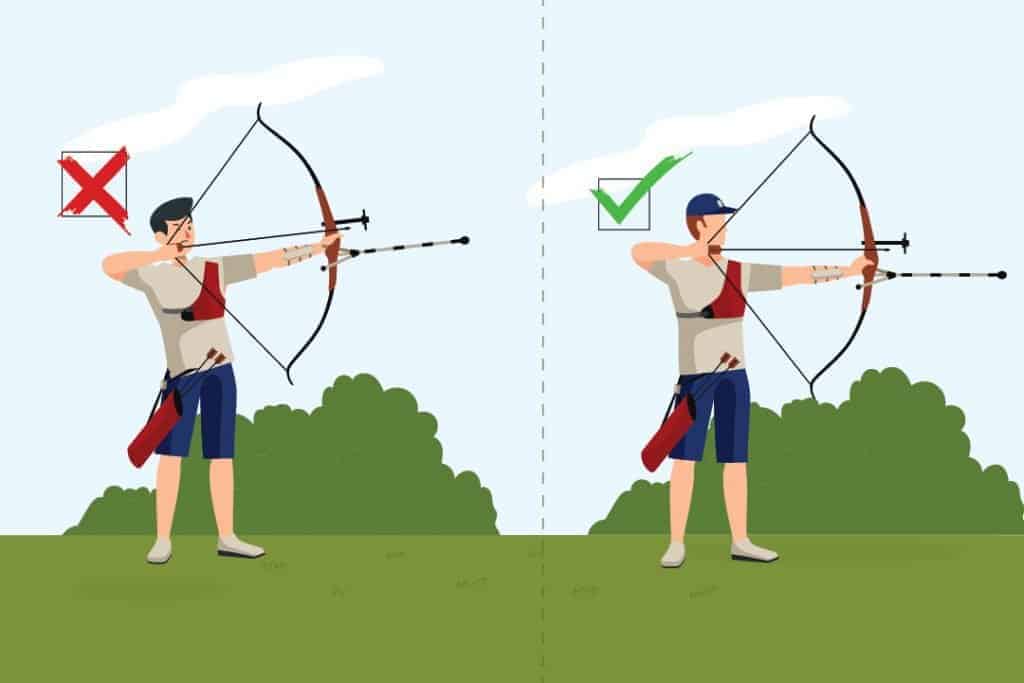

Stance

There’s no single best archery stance.

There are at the very least some basic posture elements that can help you, whichever stance you adopt, and there are four main stances that will help you get the best shots without endangering yourself.

that will help you get the best shots without endangering yourself.

The Basics:

Square Stance

Stand side on to the target. Follow your bow arm. If you hold the bow in the left arm, your left leg should be closer to the target than your right. Feet apart, in line with your shoulders, perpendicular to the target. Rotate your hips and shoulders to face the target, rather than moving your feet.

Open Stance

If you find the square stance awkward or forced, there’s the open stance. Start from the square stance, but turn the foot closer to the target, so that it’s ‘open’ like the lid on a box. Usually, something in the range of 25-30 degrees is helpful, as it feels like your hips are more open towards the target. The open stance finds a lot of favor with field archers because it can offer more stability on uncertain terrain.

Natural Stance

The natural stance can be helpful if you like the open stance, but feel frustrated by the degree of turn you still need to make towards the target. Adopt the open stance, but as well as turning the front foot by the 25-30 degrees, turn the back foot to match it. That should give you a more comfortable stance in relation to the target.

Closed Stance

Not getting the draw length you feel you need? Try the closed stance. Where in the open stance you turned the front foot by 25-30 degrees, here, you keep the front foot perpendicular, but turn the back foot by a similar degree. That will give you the additional draw length you feel you’re missing, just from a change in your stance.

Grip

Proper bow grip can help you significantly reduce the twinge, tweak, or overreaction you add to any shot.

Rest the bow against the pad of your hand. The reason for that is twofold. Firstly, it crosses fewer muscles that can twinge on release and alter the shot. And secondly, if you do something as simple as this, it’s repeatable, so you won’t vary hugely from shot to shot.

Relax your hand. Tension is equal to torque in a bow grip, and torque will throw your shot off course. Don’t give your bow a death-grip. Rest your fingers around it, so that it’s secure, but not introducing torque. You don’t need to add anything to the power of your shot through your grip. The power comes from the draw with your other hand. Let the grip be fluid, so you’re not self-sabotaging every shot you take.

Draw

Fluidity is the ideal in drawing your bow. It’s worth mentioning that while it’s fine to draw an empty bow, you should never fire an empty bow. It may damage you, and it will probably damage the bow. So assuming you have an arrow nocked, keep your bow arm straight. There’s no need to fully lock out your elbow. Keep your bow arm straight, but not rigid. Bend your bow arm, and you’re not only going to be inconsistent from shot to shot, but your draw length is going to change regularly too, meaning any success you have is going to be more or less a fluke.

Make sure all the knuckles of your bow hand are visible to you, roughly 40-45 degrees to the floor. Again, this helps with consistency and repeatability of practice. That translates over time into fluidity of movement and accuracy of shooting.

Aim your arrow at the target before you draw back your bowstring. That means you’ll only have to make minimal adjustments to your aiming before you loose the arrow.

Keep the elbow of your tab arm (the arm pulling the bowstring, as opposed to the bow arm, which is holding the bow) higher than the line of the arrow. Why? Because you have back muscles, and elevating the elbow brings them into play, so you’re not relying only on the muscles in your arm to get a comfortable draw. As you elevate the tab elbow, the bow arm should naturally feel like it’s pushed towards the target.

This can be tricky at first, but the more you do it, the more it becomes a single, fluid process. And the more singular and fluid the process, the more likely you are to hit your target.

Anchor

We’ve said that fluidity and consistency are of key importance to best practice in archery. That’s as true for where you anchor your draw as it is for any other element of the sport. If you draw to your nose for one shot, and your cheek for another, you’re going to get two entirely different shots and lack consistency.

Practice finding your comfortable release point in your hand. You’re looking for the position that’s comfortable for you, so that you can perform it with consistency, rather than with consistent pain. Find the spot, and you’ll be able to place your release correctly every time.

If you’re drawing so your hand touches your face, remember you need to make consistent contact. If you barely touch your face one shot and dig your hand into your cheek the next, you’re just inviting irregularity into your archery. Find the spot that’s comfortable and do it time and time again, whatever your initial results might be. The results you can tweak with practice. Getting consistent form though is a must.

If you’re drawing so that the string touches your face, similarly, consistency of practice is key. Lots of people draw the string to their nose – mostly because the nose is a highly convenient spot that gives you repeatable shooting.

It almost doesn’t matter what you do to anchor your draw, so long as whatever it is, you do it consistently. So above all, find a comfortable anchor point and stick with it.

Aim

Eye

Aiming can be a complicated business, depending on the kind of bow you’re using.

When you start out, it’s likely you’ll be using a standard recurve, and probably, you’ll be shooting target archery. The best way to hone your eye and your aim in those circumstances is to shoot. A lot.

That way, you’ll learn where you need to aim to get which particular results at a particular distance, without things like the wind to take into account. Practice, practice, practice. Shoot every arrow you can, adjust your aiming point shot by shot till you’re consistently getting the result you want. Then change the distance of the target and start again. That way you’ll develop an instinctive muscle memory of distances and aiming points, all else being equal. And from there, you’re just adjusting for conditions.

Bow Sight

A bow sight exists precisely to make aiming as easy as possible. Look through the sight with your dominant eye, meet the pin to the target, and release.

If your sight isn’t 100% accurate when you first line it up, see where your arrow landed. Then chase it – replicate the distance between your lined-up pin and the point where the arrow struck, and compensate accordingly.

There will be a difference between aiming with a recurve and aiming with a compound bow – usually with a recurve, you’re aiming for a fluidity of movement that leads to fast firing, so the aiming is relatively minimal. On a compound bow, once you’re at full draw, you’ll usually have a few seconds to get the aim more precise.

Either way, let your aim be part of a natural process, and stay relaxed through the aim, the draw, and the release. The last thing you want is to add stress and torque into the shot.

Release And Follow-Through

Consistency is key to every aspect of best practice in archery.

So with the release, you need to establish where you place your fingers on the string, and then return to that, time and time again. If you’re looking for perfect practice, aim for inside the first joint of your index finger. You may not get that position regularly – many archers don’t. But it’s worth aiming for this point, as it’s the most efficient place to put your fingers when releasing, and if nothing else, if you’re aiming to do the same, familiar thing time after time, you’ll probably get consistent results wherever you actually use.

If you engage your back muscles, you’re easing the pressure on your tab arm with each shot. You’re also ensuring a smoother motion, and a cleaner, more repeatable release.

Keep your hand relaxed through the draw, the aim, the release, and the follow-through, and your arrow will fly more true to its target. Tense up, and you transmit the tension to the string, to the draw, to the arrow, and to the shot.

Common Mistakes In Archery

Newsflash for you. You will get things massively wrong. Your whole career in archery is an exercise in getting fewer things wrong, building muscle memory, building knowledge. But things will sometimes still go wrong

Here’s a handful of the top mistakes people make. Don’t feel bad. Don’t focus on the mistakes you make. Every archer makes them at some point. You’re always as good as your next shot.

1. Aiming collapse

You know where you’re aiming when you’re at full draw. Then you release, and the aim goes wild or wide. Keep your focus on your aim point all the way through the release and follow through to minimize aim collapse.

2. Overaiming

Don’t overthink it. Get in your own head too much and you can worry yourself to a miss. Fluidity and consistency are the keys to performance in archery. Don’t let your own mind get between you and the fluidity of your shot.

3. Overholding

If you hold your shot at full draw too long, two things happen. Firstly, your brain kicks in and you start to overthink. And secondly, your muscles start to feel a strain with which they’re unfamiliar. Strain can equal pain, wobbles, tension – and all of those can negatively affect your shot.

4. Winds of change

If you’re shooting outdoors, and you know there’s a wind factor to compensate for, take it into consideration beforehand, but once you’ve committed to your aiming point, go with it. If you try and fight the wind second by second, it will win. And then you’ve lost a battle of wits against wind. Consider it, absolutely, but don’t recalculate second by second to fight the inconsistent wind.

5. Technology Over Technique

We know it’s tempting to get the latest piece of tech assistance, and we’re not saying you shouldn’t get it. But don’t rely on all the shiny kit to make your shots for you in spite of poor technique or sloppy form. Get technique and form right first – and maintain it throughout your career – and the tech will be a genuine addition to your game. Rely on the tech to boost your scores, and all you’re doing, ultimately, is adding a drag factor to the machine.

Archery Competitions Around The World

When it comes to finding competitions to test your mettle, a lot of the time, the answer is in plugging yourself into the right organizations.

We all know the Olympic Games classes archery among its summer sports. If you think you have what it takes, why not try out?

classes archery among its summer sports. If you think you have what it takes, why not try out?

For a worldwide take on other archery events and competitions, check out the World Archery event calendar . World Archery is the international governing body for archery, so you can be sure if it’s a big event, it’ll be on the calendar.

. World Archery is the international governing body for archery, so you can be sure if it’s a big event, it’ll be on the calendar.

USA Archery , previously the National Archery Association, keeps an active diary of events around the US. Apart from its main calendar, it also has a specific competition calendar for traditional archery competitions

, previously the National Archery Association, keeps an active diary of events around the US. Apart from its main calendar, it also has a specific competition calendar for traditional archery competitions . Longbows at dawn, archers!

. Longbows at dawn, archers!

Want to compete in American field archery events? The NFAA (National Field Archery Association) has you covered.

has you covered.

If you’re a mounted archery competitor, the Mounted Archery Association Of The Americas has an event diary you’ll want to keep bookmarked.

has an event diary you’ll want to keep bookmarked.

Conclusion

We said at the beginning that archery had begun as a human instinct to get more protein, evolved into a discipline of war, either for conquest or self-defense, and had continued adapting, into a sport, a hobby, and a fun way to spend your time.

It’s all of those things and more. It’s varied, so there’s a type of archery that will make sense to you and spark your interest. It’s challenging – and you control how far you go with it and when. And in a world which sometimes feels out of control, it can be a fantastic way to focus your mind and body.

It’s not among the cheapest of sports, because it’s equipment-centered. You can’t shoot a bow…without investing in a bow. You can’t shoot arrows, for the most part, without buying arrows. Depending on your needs and set-up, there will also be protective gear, stabilization, sight aids, even your own targets if you have the space to shoot safely at home.

If you want to shoot regularly with others, you’ll probably also have to pay for membership of local clubs or chapters. And to compete even in local events, there will be entry fees too. If you get further into archery, you could be looking to make your own custom arrows, so you can fit the tips you want, the fletching you want, and the nocks you want.

So is it a sport only for the rich? Absolutely not. You can start in archery with a try-out session or two at your local club, and they may well have club bows you can use until you get a feel for the bow with which you want to start on your journey. After that, like all sporting hobbies, the level of your expenditure is up to you. Start basic, and level up. Likewise with your time, you can start small with archery – try a session once a week. The more into it you get though, the more you’ll want to spend time practicing your form, your aim, your distances. The more you’ll want to master your bow or bows. Both on your own and with others, archery is a hobby and a sport that can become a positive addiction as you progress and get better.

Start small, level up, shoot straight. Archery’s a gift from the dawn of human civilization. Why not be part of that story?